On Wednesday, we spent some time in class talking, discussing, observing, and hopefully learning about paragraphing. It was a fun lesson for me, as a teacher, and I thankfully got lots of good feedback from students as well. I took some pictures of the notes, of which two are below.

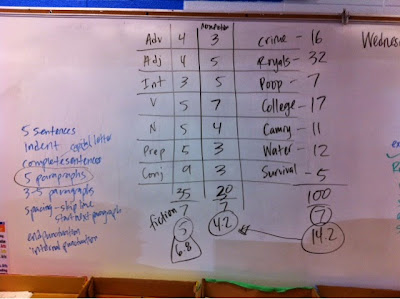

We started thinking about what teachers tell students about paragraphing. That's listed in the top picture in blue. Students came up with things like: must be 5 sentences, must indent, essays must be 5 paragraphs, and in some classes students pointed out the names of different paragraphs--opening or introduction, closing or conclusion, and body in the middle. It was nice to hear that students remembered some of what they've been taught, even if it doesn't always make it to the page or I don't agree with it.

Then I asked the students to guess how many paragraphs might be on any random page in a "normal" text (what a librarian might call a chapter book maybe, either fiction or nonfiction). Those numbers are in the top picture, in the grid on the left. Then I had the students turn to a random page and count the number of paragraphs. I didn't keep that list of numbers, but you can see that the average was a bit higher than their original guess. We then did the same for nonfiction articles--their guesses are the second column and the article counts are the far right. The averages are significantly different, which is exactly what I wanted the students to see.

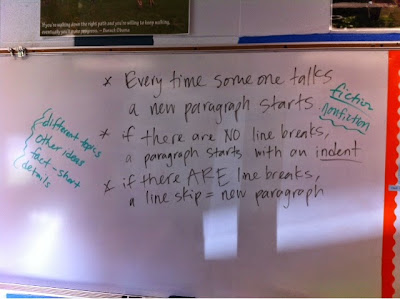

After we made these observations, we needed to try to answer some questions, so we could learn from the texts and apply that learning to our own writing. So I basically just asked the question: why? Why are there more paragraphs in fiction than we originally thought? Why are there so many paragraphs in a nonfiction text? This led to another question--how do we know there's a new paragraph?

The answers were all based on observations from students, and I'm super proud of them. The class went well, and lots of focused discussion took place. Meaningful questions were raised, and observations from our books led us to some answers. But the answers are not right/wrong or black/white. The answers could apply in one situation, but not in another. And that makes me happy as a teacher, because it means the students are understanding that there are nuances to writing based on the situation, which is likewise based on the audience and purpose. Did I say it was a good day?